Incentives are, almost, everything

Coordination technologies are needed to avoid inadequate equilibria

The coordination economy refers to the sectors of the economy that are responsible for aligning people’s incentives and solving game theoretic problems (government, finance, law, management, army, etc.), as opposed to the satisfaction economy that is responsible for producing goods that people desire (agriculture, apparel, entertainment, haircuts etc.). See the previous post for the proper introduction of the distinction

Incentives are, almost, everything

The coordination economy is important because what drives civilizational progress, economic growth, and political decisions is personal incentives grinding against physical and strategic constraints. For every person, it’s the local incentives that determine his most likely actions. When you think what Russia will do next, ask what is good for Putin, not what is good for Russia. Then ask what are his constraints.

It is only because there is so little real-time legibility of the incentives and constraints of the actual decision makers, that analysts and pundits focus so much on the incentives of organisations and states. Lack of insight into local incentives of key decision makers leads to absurd notions like that China thinks and plans for centuries ahead (and then goes on to alienate previously-friendly India by attacking it with clubs to win control over a piece of high altitude desert).

However, discrete groups of humans can acquire interests of their own and, to some extent, respond rationally to incentives. For example, we can to a degree say that Germany or Apple wants something, even though at the end it is only particular humans that have wants and interests. A group of humans does not acquire interests automatically. The local incentives of individuals within a group almost always prevail. But some groups manage to acquire a level of alignment of incentives.

Groups that manage to align incentives for the sake of group preservation are known as organizations. Through natural selection the organizations that we see are those that effectively adapted coordination techniques and managed to sufficiently align the interests of their members. The primary objective of organisations is to survive. As such we can say that Russia wants to survive, cause if it did not it would have been replaced by some other organization that does.

Incentives going wrong, and right

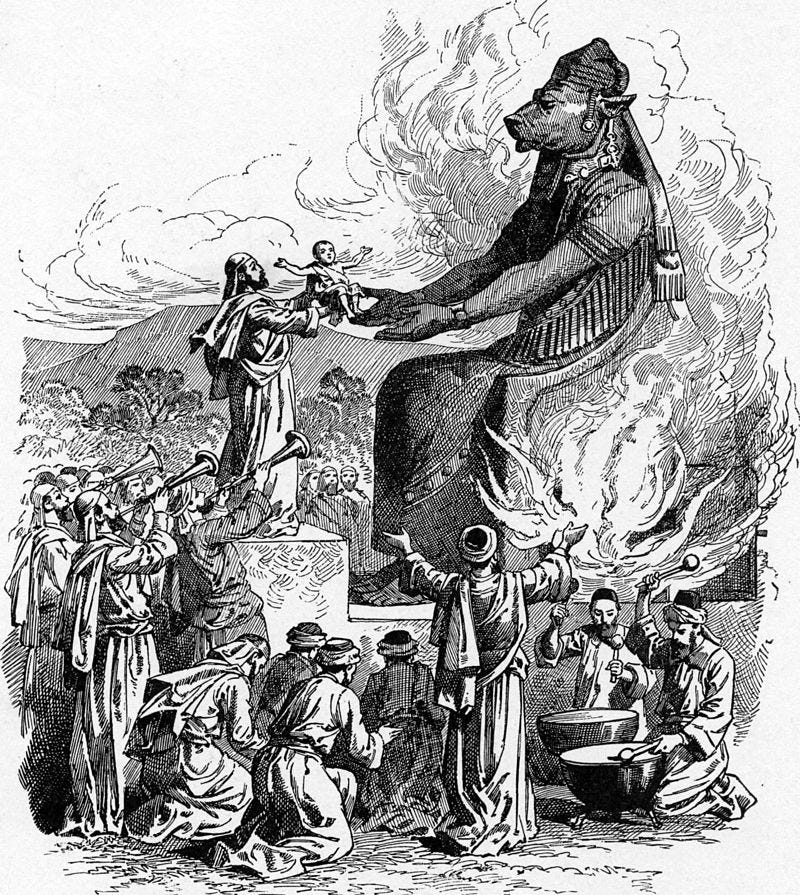

The wrong incentives result in tragic outcomes. Scott Alexander’s famous essay Meditations on Moloch describes a game-theoretic set-up that leads to sacrifice of cherished values for nothing.

In some competition optimizing for X, the opportunity arises to throw some other value under the bus for improved X. Those who take it prosper. Those who don’t take it die out. Eventually, everyone’s relative status is about the same as before, but everyone’s absolute status is worse than before. The process continues until all other values that can be traded off have been – in other words, until human ingenuity cannot possibly figure out a way to make things any worse.

Scott Alexander calls this game-theoretic set up “Moloch”, after a Canaanite god that would grant victory in war in exchange for child sacrifice. The Moloch-like incentive set-ups are a cause of much of what we see as broken in the world, including inter-state arms-races and Malthusian traps.

The human transition from hunting to agriculture, as described by James C. Scott in Against the Grain, followed a Molochian pattern. Switching from the hunter-gatherer economy to a sedentary farming existence was not an immediately attractive lifestyle switch. However, engaging in part-time farming gave early adopting hunter-gatherers a degree of food source diversification. That was the hook. The catch is that farming allows for a higher carrying capacity of a territory. So, these early, reluctant farmers had more surviving children. Over generations the resulting higher population of farmers eventually pushed out hunter-gatherers to the fringe ecological niches. Now everyone had to farm all day. Without anyone explicitly choosing the grinding labour and poverty of the farming lifestyle the Molochian incentives ensured the switch happened.

A different tragic game-theoretic set-up is when a combination of bad Nash equilibria makes the combined equilibrium especially hard to repair. Eliezer Yudkowsky in Inadequate Equilibria discusses the completely broken scientific publishing market. A monopolist company Reed Elsevier owns most of the prestigious scientific journals. It adds almost no value. All the best researchers send their manuscripts to be published in these prestigious journals. The journals derive their prestige from best researchers publishing there. The company then asks university professors to peer review the articles (at little pay), and they do it as it is prestigious to be a reviewer in the best journals. Finally, the company sells the costly journal subscriptions back to the universities where the researchers and the reviewers are employed. The company is a complete leech on the system, but no one can easily remove it. A single researcher cannot refuse to publish in the best journals because he needs to compete with other best researchers. No one university can refrain from buying the subscriptions as it would lose the best staff - researchers need to stay up to date with their discipline. Inadequate equilibria like this pop up across the economy, and are a source of huge waste, inefficiency, and misery.

When the incentives are structured well the results can be amazing. The great intellectual and artistic golden ages are usually based on a strong local economy that leaves a certain amount of slack for the privileged. But that’s not enough. For a golden age the prestige economy needs to settle on the right metrics. In any society metrics of prestige are arbitrary. In one society you made it if you own a palace with well-tended lawns, in another the ultimate prestige is to sponsor journeys of scientific discovery. I suspect the great golden ages – Periclean Athens, Renaissance Florence, the Dutch Golden Age, Enlightenment Edinburgh, the scientific revolution in Britain, the Silicon Valley in 90s and 2000s – were all driven by a society accidentally getting stuck in an equilibrium where the metric of prestige was intellectual or artistic rather than purely wealth and power based.

Adoption of coordination technologies is hard

Switching from a subpar Nash equilibrium to an optimal one is hard. Agents rarely can change the game from within. A single scientist cannot boycott the prestigious journals. Historic rival countries cannot decide to trust each other overnight. Hunter gatherers cannot stop rival bands from adapting farming. Because switching out of a bad Nash equilibrium from the inside is hard, it is difficult to develop and reform the industries of the coordination economy.

For a developing country it is much easier to achieve catch up growth in the satisfaction economy than in the coordination economy. Many developing countries have perfectly functional luxury hotels, well stocked restaurants, and world class villas for the local elites. But to produce a high-quality legal system, a well-trained army, a competent government, an efficient stock market, a stable banking system, and a low crime rate, is very rare. It requires adoption of coordination technologies.

Adapting new coordination technologies is difficult, cause it requires coordination itself. It is also extremely hard to switch from one coordination technology to another. It is almost impossible for a mature country to change from the imperial to metric system, or from civil law to common law. It requires a revolution to change from tyranny to democracy, or from central planning to free market.

Because it is so hard to upgrade the coordination technologies, the organisations that adapt the best coordination technologies gain a long-lasting advantage. Others cannot easily adapt their coordination technologies, even when their superiority is obvious.

The best organizations are those that have mastered frequent adaptation of new emerging coordination technologies. To improve is to change, to be perfect is to change often.

In the future installments of this newsletters we will look into the history of coordination technologies and speculate on the currently emerging ones.